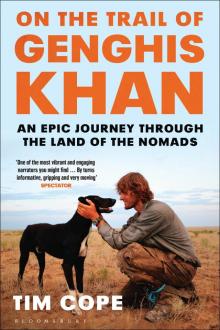

On the Trail of Genghis Khan Read online

Praise for On the Trail of Genghis Khan:

Winner of the Grand Prize at the Banff International Mountain Book Festival 2013

‘It is a vast journey, a vast, baggy book, enjoyably meandering in an age of Twitter soundbites. Cope›s journey becomes a monumental quest as he is buffeted by vicissitudes and transformed . . . The result is by turns informative, gripping and very moving: a major endeavour that flings off the straitjacket of its subgenre and stands (or rides) alone’ Spectator

‘What makes this book special is Tim Cope’s quest to understand the nomadic societies of the steppes and how their traditions survived the Soviet era, his feeling for the people he meets and his keen eye for the poetry of the landscape . . . This wonderful tale is full of mind-expanding horizons and insights into the complex freedoms and precarious future of the nomadic lifestyle’ Sydney Morning Herald

‘Cope speaks impassionedly of the duality of the steppe, the extremes of its weather, its history, the cruelty and kindness of its peoples, as well as the marginalisation of nomadic culture’ West Australian

‘As well as being a thrilling boys’ own type of adventure, On The Trail of Genghis Khan also offers much fascinating history about the great marauder Khan and about Central Asian culture and geography. Cope is obviously in love with the landscapes he encounters . . . An endless, rollicking adventure of a delightfully old-fashioned type, and I defy you to read it and not want to book your passage to the wilds of Lake Balkhash’ Good Reading

‘Through all these travails, his calmness and simple humanity kept him moving. Absolutely absorbing travel adventure’ Courier Mail

‘Tim Cope details the psychological and physical hardships he endured . . . Inside are stories that range from funny to dire as he travels the length of the steppe’ Australian Geographic

DEDICATION

In June 2004, at the age of twenty-five, I set out to ride on horseback from Mongolia to Hungary, approximately 10,000 km, across the Eurasian steppe. I called it the “Trail of Genghis Khan,” referring to the inspiration I found in the nomadic Mongols, who under Genghis Khan set out to build the largest land empire in history. The aim of my journey was to honor and understand those who have lived on the steppes with their horses for thousands of years, carrying on a nomadic way of life.

When I reached the Danube more than three years later, in autumn 2007, one of the common questions people asked me was, “How did you cope for so long alone?” The truth is that I never thought of myself as being entirely alone. With me were my family of horses, two of whom, Taskonir and Ogonyok, carried me most of the way. Then there was Tigon, my Kazakh dog, who accompanied me on his own four feet. My animals were on the front line of this journey, bearing the brunt of the extremes of cold and heat, traversing deserts and mountains, and being subjected to the consequences of bungled bureaucracy and even horse thievery. It was through them I came to experience the tapestry of the Eurasian steppe, and in retrospect, I can think of no better explanation for my journey than the reward of riding with my steeds, Tigon running by their hooves, as we sailed over open steppe, where nothing—not thoughts, feelings, time, the earth, or animals—was fenced in.

It is also true that the journey would have been meaningless without the many individuals and families I met, several of whom joined me for parts of the way, and more than one hundred of whom took me and my animals in. Some of my hosts were desperately poor, others were rich, and many were afflicted by alcoholism or even involved in corruption and crime, but most cared for me like I was a friend and shared their food, fodder, and shelter generously—sometimes, as it turned out, for weeks and months. To be welcomed with a smile by a stranger after many days of hard riding, even though I was usually in a state of disrepair, provided a sense of camaraderie and closeness that not only enriched my life but in some cases saved me and the lives of my animals.

All of my hosts also shared the story of the circumstances of their lives, their culture, and their history with great honesty and openness. I realized later on that in some of them I had met the modern guardians of the steppe—those special people who are driving the culture into the future, fueling the pride of the nomad, saving the traditions, and keeping the memory of their ancestors alive.

This book is dedicated to all of these people I met on the Eurasian steppe, and to my animals.

Before us now stretched Mongolia with deserts trembling in the mirages, with endless steppes covered with emerald-green grass and multitudes of wild flowers, with nameless snow peaks, limitless forests, thundering rivers and swift mountain streams. The way that we had traveled with such toil had disappeared behind us among gorges and ravines. We could not have dreamed of a more captivating entrance to a new country, and when the sun sank upon that day, we felt as though born into a new life—a life which had the strength of the hills, the depth of the heavens and the beauty of the sunrise.

—Henning Haslund

Mongolian Adventure: 1920s Danger and Escape

Among the Mounted Nomads of Central Asia

Contents

Map

Mongolia

1. Mongolian Dreaming

2. The Last Nomad Nation

3. Wolf Totem

4. A Fine Line to the West

5. Kharkhiraa: The Roaring River Mountain

Kazakhstan

6. Stalin’s Shambala

7. Zud

8. Tokym Kagu Bastan

9. Balkhash

10. Wife Stealing and Other Legends of Tasaral

11. The Starving Steppe

12. The Place That God Forgot

13. Otamal

14. Ships of the Desert

15. The Oil Road

Russia

16. Lost Hordes in Europe

17. Cossack Borderlands

18. The Timashevsk Mafia

Crimea

19. Where Two Worlds Meet

20. The Return of the Crimean Tatars

Ukraine

21. Crossroads

22. Taking the Reins

23. Among the Hutsuls

Hungary

24. The End of the World

Epilogue

List of Maps

Acknowledgments

Image Section

Glossary

Selected Bibliography

Notes

A Note on the Author

By the Same Author

Map

Mongolia

1

MONGOLIAN DREAMING

Only ten minutes earlier we had been bent forward over our saddles, braced against the nearly horizontal rain and hail, but now the afternoon sun had returned and the wind had gone. As I peeled back the hood of my jacket, details that had been swept away by the storm began to filter back. Nearby there was the rattle of a bridle as my horse shook away a fly; around us, sharp songs floating through the cleansed air from unseen birds. The wet leather chaps around my sore legs began to warm up, and the taste of dried curd, known as aaruul, turned bitter in my mouth. Ahead, my girlfriend, Kathrin, sat remarkably calm on her wiry little chestnut gelding. Below, the rocking of my saddle as my horse’s hooves pressed into soft ground was steady as a heartbeat.

In a land as open and wide as Mongolia I was already becoming aware that it took just the slightest adjustment to switch my attention from the near to the far. With a twist in the saddle my gaze shifted to the curved column of rain that had been drenching us minutes before, but which now sailed over the land to our left. Pushed out by the wind in an arc like a giant spinnaker, it crossed the valley plain we were skirting and continued to distant uplands, fleetingly staining the earth and blotting out nomad encampments in its path.

During childhood, I

had often watched clouds such as this, feeling envious of the freedom they had to roam unchecked. Here, though, the same boundless space of the sky was mirrored on the land. Scattered amid the faultless green carpet of early summer grasses, countless herds of horses, flocks of sheep and goats, shifted about like cloud shadows. For the nomads who tended to them, nowhere, it seemed, was off-limits. Their white felt tents, known as gers, were perched atop knolls, by the quiet slither of a stream, and in the clefts of distant slopes. Riders could be seen driving herds forward, crossing open spaces, and milling by camps. Not a tree—or shrub, for that matter—fence, or road was in sight, and the highest peaks in the distance were all worn down and rounded, adding to the feeling of a world without boundaries.

Clutching the reins and refocusing my sights on the freshly cut mane of my riding horse, Bor, I wavered between this simple, uncluttered reality and the trials of a more complex world that were slipping behind.

For the past twelve months I had been preparing for this journey in a third-floor apartment with a static view over the suburbs of inner-city Melbourne, Australia. In theory, the idea of riding horses 10,000 km across the Eurasian steppe from Mongolia to Hungary was simple—independent of the mechanized world, and without a need for roads, I would be free to wander, needing only grass and water to fuel my way forward.1 One friend had even told me: “Get on your horse, point it to the west, and when people start speaking French, it means you have gone too far.”

In reality, there were complexities I needed to plan for. I knew, for example, that bureaucracy—getting visas and crossing borders with animals—would likely be a major obstacle, and taking the right equipment could mean the difference between lasting two hundred days on the road or just two. Perhaps more significant were the challenges ahead that remained unknown, and of a type unfamiliar to me. At that point, early in my planning, not only was the scale of the journey beyond my comprehension, but the sum total of my experience as a horseman amounted to ten minutes on a horse almost two decades earlier, when I was seven years old. On that occasion I had been bucked clear and shipped to the hospital with a broken arm. I was still deeply scared of these powerful creatures, and couldn’t quite picture myself as a horseman—a feeling shared by my mother, Anne, who was a little bewildered when I first mentioned the idea.

Notwithstanding the uncertainties, I had pressed ahead with plans, and by the spring of 2004 I felt reasonably well prepared. With valuable direction from the founder of the Long Riders Guild, CuChullaine O’Reilly, I had studied the realities of traveling with horses and gathered together a trove of carefully selected equipment. I had also managed to make contact with people in embassies, visa agencies, and those who had promised to help me on the ground.

Not all preparations had proven fruitful. I hadn’t managed to raise enough money to reach my target budget of $10 a day (for a journey I expected to take eighteen months), and assurances I would receive long-stay visas were vague at best. Since planning had begun, it was also true that I had not accumulated as much experience on horseback as I had hoped. In addition to that disastrous long-ago ride, I had managed to join a five-day packhorse trip through the Victorian Alps in southeastern Australia—courtesy of the Baird family, who were kind enough to take on the white-knuckled novice that I was—and a three-day crash course with horse trainers and an equine vet in Western Australia. Nevertheless, I was buoyed by the firm belief that because the difficulties of the journey ahead would prove to be of a scope beyond my imagination, not even another forty years of planning would have been enough. And besides, who could possibly be better teachers than the nomads of the steppe who I would soon be among?

From the time I booked my air tickets and canceled the lease on my apartment, there had been no turning back. Life as I knew it was disassembled, and I went through the process of farewells with my family. After saying goodbye to one of my brothers, Jon, I slumped up against the wall in my emptied apartment in tears. Setting off on such a long journey as the eldest of four close-knit children, I felt as if I was severing ties, and it frightened me to think how much we might grow apart. Finally, at Melbourne airport my existence was stripped down to an embrace with my mother. The longer I lingered in her arms, the more strongly I felt that, as a son, I was doing something that bordered on irresponsible.

After making my way to Beijing, and from there by train to Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, I had spent a few weeks persuading Mongolia’s Foreign Ministry to grant me a visa extension (and very nearly failing), gathering together additional equipment, and, finally, searching for the horses that would be my transport, load carriers, and traveling companions.

A young English-speaking Mongolian man named Gansukh Baatarsuren had taken me to the home of a nomad family 300 km southwest of the city, where he promised to find me “hero’s horses.” The process had proven tricky. There was a general belief among nomads—in my case warranted—that “white men could not ride,” and upon discovering the buyer was a foreigner, several previous offers to sell had been rescinded. No one wanted to be responsible for exposing a foreigner like me to danger, let alone risk maltreatment of their prized horses.

In the end I had been helped in my quest by a stroke of luck—there had been a general election, and voting was an opportunity for nomads to ride in from all corners of the steppe to socialize. Gansukh had gone to a polling place and put word out that he was looking for three good mounts. The following day, while I hid in a ger, he covertly negotiated with sellers on my behalf. In this way I had managed to buy two geldings and had purchased a third from the nomad family with whom we were staying.

Just six days ago I had assembled my little caravan and taken the first fragile steps, albeit most of them on foot, leading my little crew. Since then I had rendezvoused with Kathrin, who planned to ride with me for the first two months of the journey.

Lifting my eyes again to the steppe between my horse’s ears, I felt the stiffness in my joints ebb away. Perhaps it was just the effect of airag seeping in—alcoholic fermented mare’s milk that Kathrin and I had been served by the bowlful during lunch with nomads—but for the first time since I’d climbed into the saddle, a sense of ease washed over me. With reins in hand, compass set, and backpack hugging me from behind, all I could think was that ahead lay 10,000 km of this open land to the Danube, and across all of these empty horizons, not a soul knew I was coming.

When the sun began to edge toward the skyline and the heat wilted, I watered the horses, then chose a campsite halfway up a hillside that overlooked the country we had ridden through. As would become my regular evening routine, I set about hobbling the horses and tethering them around the tent using 20 m lines and steel stakes. The camping stove was fired up, dinner was boiled, and Kathrin and I rested up against the pack boxes to watch herds of sheep and goats pouring over troughs and crests on their way back to camps scattered below. The sweet smell of burning dung and calls of distant horsemen carried through to us on the breeze, and when our dinner pots had been scraped clean, we lay down on mattresses of horse blankets listening to the crunch of horses chewing through grass. Thereafter the prospect of unbroken weeks and months of travel held me lingering in a dreamy state of semiconsciousness.

I must have eventually fallen into a deep sleep, for when I opened my eyes again, the bucolic scenes of evening had vanished. In their place the tent clapped and bucked in a roaring wind. Something had woken me, and although I wasn’t sure just what, I crawled out of my sleeping bag and clutched blindly for my flashlight. When I failed to find it I lay still, held my breath and strained to listen for my horses.

Minutes passed. There were no telltale jingles of the horse bell that had been tied around the packhorse’s neck, or indeed any other sound indicating the horses were grazing. I tried to convince myself I was experiencing a moment of paranoia and that the horses were sleeping, but then from somewhere beyond camp I heard muffled voices and the thunder of hooves. I forced my way out and ran barefoot to where I had tethe

red the animals, only to find my white riding mount, Bor, alone, pulling at his tether line and madly neighing into the black of night. Somewhere beyond the perimeter of camp the sound of galloping was fading fast.

Holding Bor’s tether tight, I stumbled my way farther until I felt the other two tether lines between my toes. When I reached the end of one I fell to my knees clutching the only remaining evidence of the other two horses: the bell and a pair of hobbles.

Even as Kathrin woke and came running from the tent with a flashlight, warnings I’d brushed aside from seasoned nomads in recent days came flooding back: What are you going to do when the wolves attack? When the thieves steal your horses? Are you carrying a gun? In response I had naively pointed out my axe and horse bell. Sheila Greenwell, the equine vet in Australia who had so kindly helped me prepare, had suggested that if I put the bell on my horses at night I would wake up if thieves did approach, because the horses would become nervous and sound the bell. In reality, the sound of the bell as the horses grazed in the dark had led the thieves straight to my camp. They had quietly slipped off the bell, untied the horses, and made their escape.

As futile as it might have been, Kathrin and I continued to trawl the steppe in the hope we might have missed something. But by the time we returned to the tent, frozen, there was no denying that on just the sixth day of my journey some of my plans needed revision. In fact, I thought, perhaps the whole journey needed a rethink.

The vision of riding a horse on the trail of nomads from Mongolia to Hungary had been incubating since I was nineteen. At the time I’d abandoned law school in Australia to study wilderness guiding in Finland. There I’d learned about the travels of Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim—the legendary Finnish general and explorer who began his career in the Russian Imperial Army and went on to lead Finland’s move to independence, eventually becoming Finland’s president during the final stages of World War II.

On the Trail of Genghis Khan

On the Trail of Genghis Khan